July 22, 2025

Harold (“Hal”) Feiveson, who had been part of Princeton University almost continuously since 1961, died peacefully at his home in Princeton, July 10, 2025, at the age of 90.

Born in May 1935 in Chicago, Hal studied physics as an undergraduate at the Illinois Institute of Technology where he was an award-winning college baseball player. He went on to study physics as a graduate student at UCLA and worked part-time for Hughes Aircraft where he was asked to work on developing nuclear-armed air-to-air missiles for shooting down Soviet nuclear bombers. He later said that “this was one of my first introductions to the lunacy of the nuclear arms race.” In reaction, Hal decided to change course and work on nuclear arms control, which together with college athletics became defining features of his long career at Princeton.

Early career

Hal came first to Princeton in 1961, and in 1963 he earned his Master’s degree from the School of Public Policy and International Affairs. He then joined the Science Bureau of the U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency (ACDA), established two years earlier by President Kennedy. There he wrote the first draft of the verification protocol for what became the 1968 Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty. This imposes a system of international inspections on civilian nuclear power programs and materials to prevent their diversion from peaceful uses to nuclear weapons purposes. A key element of the global nonproliferation regime, this safeguards system is managed by the International Atomic Energy Agency, commonly known today as the United Nations nuclear watchdog.

During his four years at ACDA, Hal also came up with the idea and first draft of what became a UN Security Council resolution, which laid out an obligation on the United States and other nuclear weapon states to assist any non-nuclear-weapon state if it is attacked by another state with nuclear weapons. Resolution 255 was adopted on 19 June 1968, after Hal had left the government.

Hal also was an early critic of U.S. plans for missile defenses to shoot down incoming Soviet missiles. Together with colleagues in the Science Bureau, he worried that such missile defenses would drive the Soviet Union to build more missiles. He drafted internal papers arguing against a national missile defense program. Eventually this view prevailed, and in 1972 the United States and the Soviet Union signed the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty to limit missile defense systems. The treaty lasted for 30 years until the United States withdrew in 2002.

The Princeton PhD

Hal returned to Princeton in 1967 to do a PhD in public and international affairs. During this period, Vietnam War issues were roiling the campus, Students protests and a sit-in targeting the Princeton offices in the Engineering School’s Von Neumann Hall of the Institute for Defense Analysis, a military contractor doing classified research, led to thirty-one students being arrested. Professor Thomas Kuhn (of scientific revolutions fame) was asked to review the University’s relationship to the Defense Department. Kuhn asked Hal to help him. Their main recommendation was to end classified research on campus. This has been Princeton policy ever since.

Hal’s 1972 PhD thesis Latent Proliferation: the International Security Implications of Civilian Nuclear Power focused on what he described as “the dangers inherent in the spread and intensification of civilian nuclear power [since] civilian nuclear power programs provide a foundation for the development and production of nuclear weapons.” He was concerned in particular about the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission’s proposal for a fleet of reactors that would be fueled by plutonium rather than uranium and that also would produce or breed additional plutonium. Plutonium can be used to fuel nuclear weapons; the fission of only one kilogram in a U.S. atomic bomb destroyed the Japanese city of Nagasaki on August 9, 1945.

Hal’s concerns were soon proved prescient. In the spring of 1974, India used plutonium produced and separated with AEC assistance to power its first nuclear weapon test.

Policy research and action for a safer world

In 1972, Hal became a founding member of Princeton’s new Center for Environmental Studies being set up by Professor Robert Socolow. Physicist Frank von Hippel joined the Center in 1974 and soon began working with Hal on the plutonium issue. The two founded a Program on Nuclear Policy Alternatives within the Center, which was based in the Engineering School’s Von Neumann Hall space vacated by the Institute for Defense Analysis. In 2001, the Program on Nuclear Policy Alternatives became the Program on Science and Global Security (SGS) and formally part of the School of Public and International Affairs.

With Socolow’s support, Hal and von Hippel recruited energy policy expert Robert H. Williams and former nuclear weapon designer Theodore B. Taylor to join them. In 1976, the four wrote a seminal article, “The plutonium economy: why we should wait and why we can wait.” They went on to help educate President Carter’s White House. The four then worked with a group of NGOs that helped persuade Congress to end of the U.S. breeder reactor development program in 1983.

Proliferation was not the only nuclear danger to draw Hal’s attention. In 1981, the Reagan Administration came into office convinced of the need to more forcefully confront the Soviet Union. The administration ordered 10,000 new accurate nuclear weapons to destroy Soviet nuclear weapons before they could be launched.

Given this alarming situation, Hal worked with von Hippel on nuclear arms control. In 1985, they wrote an article with Professor Richard Ullman, arguing that it would be possible to cut U.S. and Soviet nuclear forces by 90 percent as a first step toward nuclear disarmament and make their confrontation less unstable. Ullman reworked their argument into a New York Times Magazine article that drew praise from Secretary of State George Schultz ’42 who was key in turning President Reagan to nuclear arms control. In parallel, von Hippel took their arguments to Mikhail Gorbachev’s science advisors. Ultimately, an almost ten-fold nuclear weapons reduction was achieved.

After the Cold War, Hal continued to pursue the goal of further dramatic reductions in nuclear arsenals and saner nuclear policies. In the mid-1990s he worked with other leading U.S. arms control experts to make a plan to slash the U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals from several thousand weapons to a few hundred weapons each and to reduce the danger of accidental nuclear war. This led to a book edited by Hal, The Nuclear Turning Point: A Blueprint for Deep Cuts and De-alerting of Nuclear Weapons, published by the Brookings Institution in 1999.

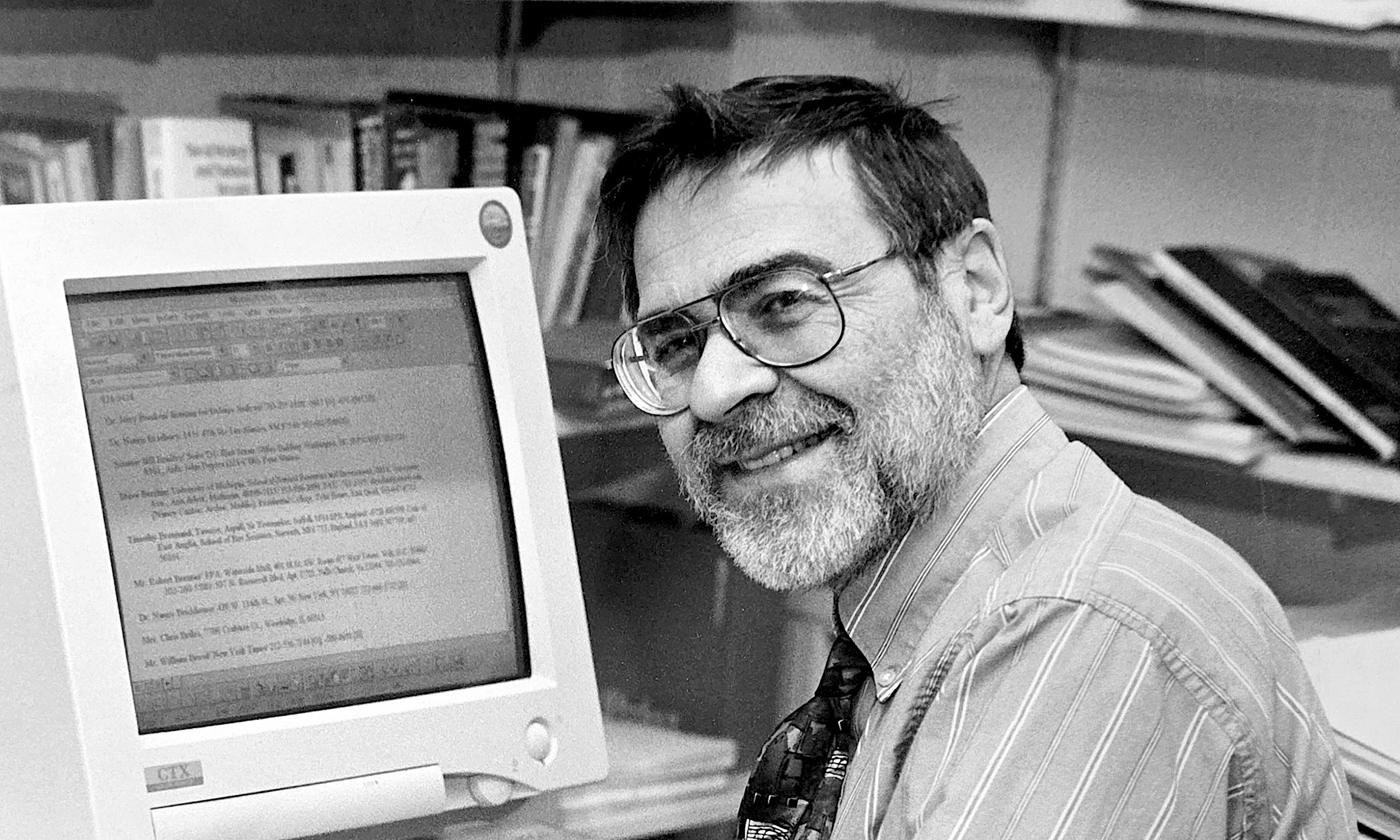

Another academic legacy of the collaboration with Gorbachev’s science advisors was the international journal, Science & Global Security. It is widely regarded as the leading international journal for peer-reviewed scientific and technical studies to support international security, arms control, disarmament, and nonproliferation policy. Hal was its editor in chief for its first twenty years.

Hal never gave up his interest in the links between nuclear power, nuclear fuels and nuclear weapons. He was an active participant in the International Panel on Fissile Materials (IPFM), a 16-country independent group of arms-control and nonproliferation experts set up in 2006 at the Program on Science and Global Security. Its mission is to provide the technical basis for policies to reduce stockpiles and end the production and use of plutonium and highly enriched uranium, the fissile materials that are the key ingredients in nuclear weapons. This work led Hal to co-author several important Panel reports and together with von Hippel and their Program colleagues Alexander Glaser and Zia Mian, the book Unmaking the Bomb: A Fissile Material Approach to Nuclear Disarmament and Nonproliferation (MIT Press 2014).

Teacher and mentor

Hal was on the Princeton teaching faculty from 1974–1981 and spent more than 30 years on the research faculty (1981–2013). He taught numerous courses, policy task forces, and graduate workshops relating to nuclear weapons, energy, and national and global environmental issues. He loved teaching and mentoring students and excelled at it. He especially enjoyed immensely drawing other scholars and experts into the teaching process, thus enriching the experience for both the students and himself.

For years Hal led undergraduate policy conferences in the School of Public Policy and International Affairs where upperclass students took different sides of a real current issue and negotiated a policy to ameliorate the situation. Former SPIA Dean Anne Marie Slaughter, as a junior, took such a class led by Hal. On hearing of his death, she recalled: “I can still remember the atmosphere he created in the classroom and the way he both taught and empowered us. … To revere a teacher when you are a student is not so unusual, but Hal was just as civil and decent, and yes, gentlemanly, as a faculty member when I was Dean. He embodied the decency and dignity that this country is sorely lacking right now ... I grieve his loss.”

Hal arranged trips for the students to meet experts. Often these trips were to Washington, DC, but some trips were international. In 1980, Hal took a group of juniors to London, Brussels, and The Hague for discussions of reductions of the 7,000 U.S. “tactical” nuclear weapons deployed in NATO Europe in case the Soviet army crossed the inter-Germany border. Another policy conference in (the mid 1990s) was on water rights involving Israel and the Palestinians. The class traveled to Israel and the West Bank to both understand the water situation and to speak with critical players on both sides of the issue.

Another popular freshman seminar that Hal taught repeatedly was on scientific breakthroughs during World War II. These included radar, code-breaking, anti-submarine warfare and, of course, the atomic bomb. In 2017, he published the book Scientists Against Time based on his course.

Hal also taught freshman seminars on topics outside of his research area but of personal interest to him. One of these was “Ethics in Collegiate Sports” which he taught with Jeff Orleans, then the Commissioner of Ivy League Athletics. Orleans recalled “I was day-to-day impressed by how much I learned from Hal about how to teach, and especially how to teach in a seminar environment. How to help these smart young folks sometimes come out of their shells, sometimes just the opposite, be a little less competitive, but mostly help them learn. To really push and see what the questions were and what the answers were.”

Hal was an avid fan of Princeton sports—particularly of the basketball teams. In his role as Academic Fellow to the men’s team, he provided academic guidance to a number of team members. Some went on to major careers in sports: Will Venable, who played baseball as well as basketball at Princeton, played for the San Diego Padres, the Texas Rangers and the Los Angeles Dodgers and currently manages the Chicago White Sox. Venable reflected “Professor Feiveson was more than a professor—he was a lifeline. He went above and beyond to be there when any member of the basketball team needed help—whether it was offering feedback on papers, running through ideas or simply, talking through issues we might have with a class. There’s no way I could have survived without his guidance to navigate the academic challenges.”

Another basketball-player advisee, Steve Mills, became president and chief operating officer of Madison Square Garden and returned to Princeton to co-teach a freshman seminar with Hal. In recognition of his role in support of Princeton’s student athletes, in 2010, Hal received the Marvin Bressler Award from the Department of Athletics.

Hal had eclectic interests, a kindness and talent for collaboration, and a gift for friendship. He hobnobbed with Princeton scholars from many disciplines ranging from mathematician John Conway to sociologist Marvin Bressler, legal historian and scholar of culture Stanley Katz, and military historian Paul Miles. He also was close to Freeman Dyson, the legendary free-wheeling Institute for Advanced Study's physicist, who often came to speak to his class.

He is survived by his wife Carol of 51 years, their children Dan, Peter and Laura and their four grandchildren.